How much do you know about what is in the water in your taps?

Written by: Madeline Nowak, Sustainability Editor

Photos by: Grace Metcalf, Caleb Upson, and Madeline Nowak

A tour of the Clifton Water Treatment Plant with District Manager Ty Jones and Water Treatment Operator Isaac Brown detailed the process of water treatment from start to finish.

Where It Starts

The water fed into the plant comes from one of two places initially. During irrigation season, from April to November, the water is piped in from the canal. The rest of the year, the water comes directly from the Colorado River. The plant is all gravity fed, which means there is very little energy needed to get the water to the plant.

Some of the water is fed into a pond that sits next to the treatment buildings. The pond stores the water until it can be treated and also helps to purify the water that goes into it. In fact, the pond cuts the dirt in the water stored in it by half. The pond stores about 4 million gallons of water, which means about a day and a half of water during winter, and half a day of water during the summer, when water use is high.

The rest of the water is sent straight to the treatment buildings, to be processed.

The First Building

The process begins with what’s called an aluminum sulfate flash mix chamber. Aluminum sulfate is a coagulant, meaning it’s positive charge attracts the negatively charged dirt particles in the water, bonding the dirt into cloud-like groups that the engineers call the flock.

The water flows down a long serpentine path, giving it time to coagulate. At the beginning of the path, the water is moving faster, while farther down the path it is deliberately slowed, so that the flock doesn’t break apart, which would defeat the purpose of coagulation in the first place. The point is to form heavy sediment that will fall out to the bottom of the water, not to break up that same sediment.

After it’s coagulated sufficiently, the water is moved through angled sheets that force the water up and the sediment down, speeding up the process that was started in the flash mix chamber. At the beginning of the path, the water has a turbidity (sediment content) of 129 ntu and by the end it has a turbidity of 0.5 ntu. For context, drinking water should have 0.5 ntu or less. The water will be further filtered in the next portion of the process.

The Second Building

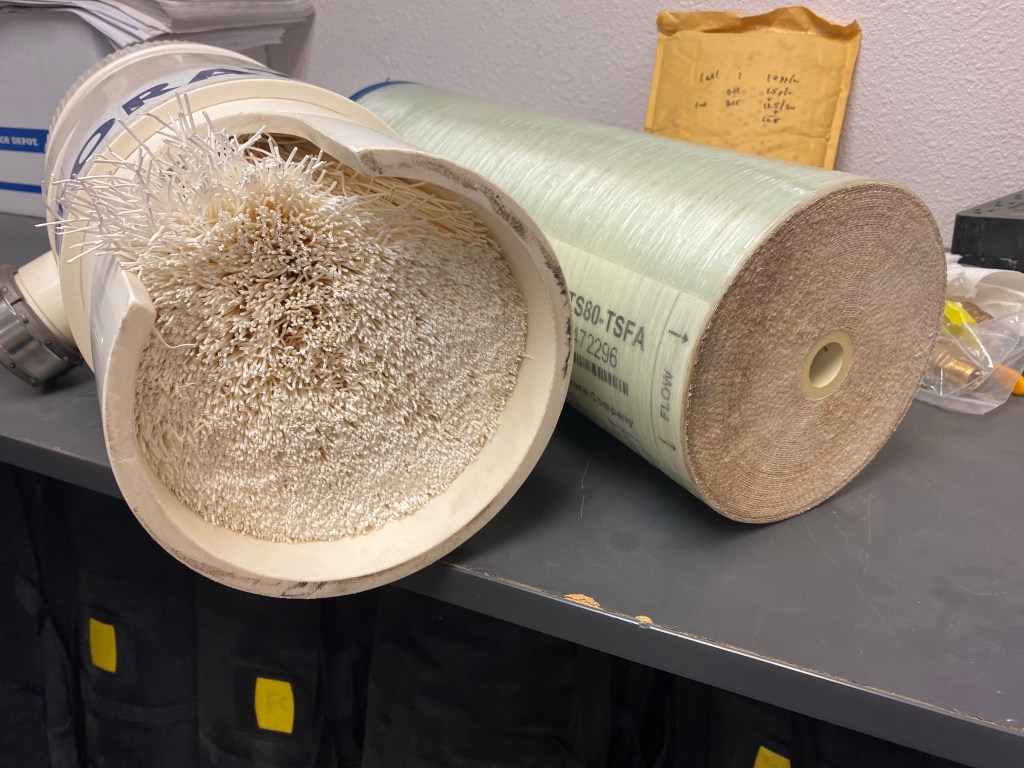

Moving to the next building, the water is pumped through strainers that remove any remaining large particles or fish before the water is sent through the treatment plant’s main feature: the membranes.

There are dozens of thick tubes that contain hundreds of membranes, which are like tiny straws with microscopic pores all along them. The pores are 0.02 microns, which is an absolute filter, as there are no bacteria or viruses under 0.02 microns. After the filters, the water has to have a turbidity of under 0.1 ntu most of the time and never above 0.5 ntu. The turbidity on the day of the tour was 0.0106 ntu.

However, the state mandates a multi-barrier approach to filtration of viruses and bacteria, so the water is then chlorinated and sent through another long serpentine path, underneath the floor of the plant, to make sure there are no viruses left.

Before the water leaves the plant, three things are added to it. First, zinc orthophosphate, to ensure that the water doesn’t pick up any chemicals from the pipes that it is sent through on the way to consumers. Second, fluoride to help with dental health. And third, chlorine to keep the water fresh on the way to the consumer. The last one is state mandated as well, so the chlorine content of the water must be above 0.2 milligrams per liter throughout the entire system.

Where It Ends

After the water is done in the treatment buildings, it is sent to one of two places. Either it goes directly to consumers, or it is sent through one last process called reverse osmosis. Reverse osmosis is one of the most energy intensive processes on the plant, but it serves an important purpose. The water that goes through reverse osmosis is incredibly pure. It removes any remaining carbon compounds and it also removes PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) which have been linked to some health risks. Actually, the water that comes out of the reverse osmosis process is too pure, which is why it is then sent into the same pipes as the water that did not go through the process in controlled quantities. Plant operators mix the two purities of water in particular portions to keep the hardness of the water at 120 parts per million at all times, so that consumers get the most consistent water possible.

Treatment plant operators monitor the treatment plant and the water in the pipes all the way through the process. Clifton’s plant operators have advanced degrees in biology, chemistry, and even one aerospace engineer. They monitor and adjust the contents of the water and keep an eye on water age, to ensure the water is as fresh as possible when it gets to consumers.

As the topic of water comes more into focus in society, it’s important to know what goes into the water you use every day.