By Will Locascio, Arts and Entertainment Editor

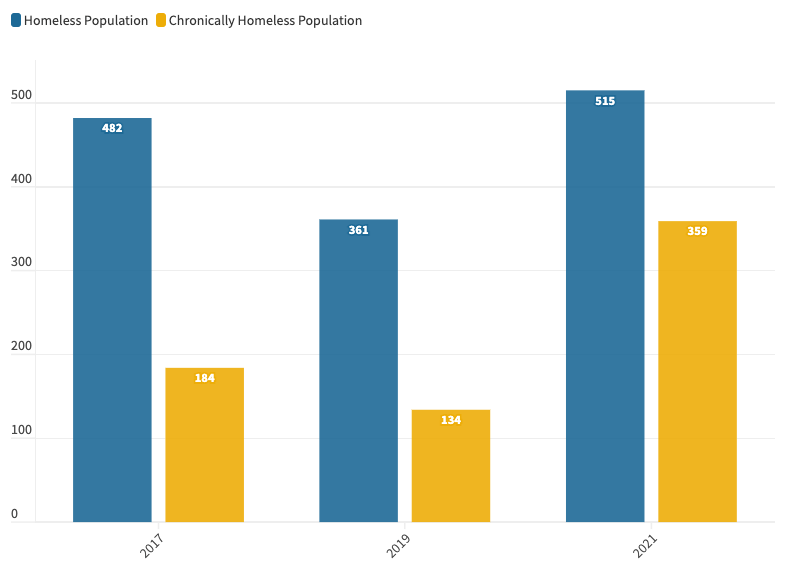

In 2020, homelessness in Grand Junction was a brewing problem, an open electrical socket simply waiting for a spark. The COVID-19 pandemic proved to be the very spark needed to nearly triple Grand Junction’s homeless population in the course of two and a half years. On top of COVID-19, the city’s complete lack of resources for harm reduction and mental health services lead the citizens of this town to chronic homelessness. A recent study released by the Common Sense Institute highlighted that in 2019, only a quarter of Grand Junction’s total homeless population were unsheltered as well. Unsheltered in this context means the percentage of the homeless population who have no access to a shelter bed or basic medical care. Now, three years after the homeless population spike of 2020, over 60% of the population is unsheltered. Despite the ever increasing number of Grand Junction residents finding themselves in chronic homeless situations, the primary developments from the city’s side have been the Coalition for the Homeless rebranding how they refer to those in housing crisis from, “Homeless,” to “PEH,” an acronym that breaks down to “Person Experiencing Houselessness.”

The homelessness crisis in Grand Junction is being worked on from the city’s side by the housing department as well as the Coalition for the Homeless, a monthly gathering of dozens of organizations from Grand Junction who work to collect data and create plans to try to shelter Grand Junction’s chronically homeless. The March gathering of the Coalition for the Homeless was underwhelming from a productivity standpoint. The local Catholic Outreach laid out their process of interviewing the chronically homeless and assessing the vulnerability and danger level each are in, followed by an appeal to the other organizations at the meeting for donations to help with their battle to fight homelessness. The next day, activists helping the homeless population at Whitman Park discussed how Catholic Outreach are using their donation money to build a costly new church that is only a block away from the park, which has come to be known as “Bum Park,” for many Grand Junction locals.

Whitman Park is located in downtown Grand Junction at 4th Street and Pitkin Avenue. Summer Fredlund/April 5, 2023.

Glen Grueling, a minister for Green Faith ministries used to be homeless in Grand Junction and made many references to unhelpful and unreasonable tactics being practiced within Catholic Outreach’s transitional housing services. Grueling referenced a time when he was attempting to get back on his feet and was kicked out of their housing services for smelling like marijuana. Grueling also referenced a situation where he passed out outside of Catholic Outreach temporary housing, “I was in the catholic outreach house, and I stood up to go outside and smoke a cigarette, and I passed out, I broke my hip. I didn’t have a phone so I just had to sit there all night.”

The city’s housing department spent most of their time at the Coalition for the Homeless meeting breaking down statistics from a recent census they conducted to gain a better perspective of the city’s current problem. Part of this census included interviews with homeless people from around town and found that the number one, primary universal need for these displaced people is more affordable housing across Grand Junction. This led the housing department, headed by Ashley Chambers, to a new term – coining Grand Junction a “Build for Zero,” city. This is essentially a flashy way to say they want to establish and build enough new properties to get a roof over these people’s heads who have slipped through the cracks of society.

Eric Niederkruger, a member of a local group of radical change makers called Solidarity Not Charity refuted this idea from the city saying, “Grand Junction gave 5.9 million dollars of taxpayer funding to develop luxury apartments at the old City Market. 5.9 million dollars and not one unit of affordable housing. Grand Junction believes in socialism for the rich and rugged individualism for the poor.”

Solidarity Not Charity are the true boots on the ground team of free thinkers and advocates for the homeless. Their current focalizer – as they stray away from labeling any one of them as a “leader,” for the group – is a driven woman named Pooka Cambell. Campbell has been a key member for Solidarity Not Charity for the past nine years after she was passed the torch from Niederkruger to help keep young people involved in the community and assisting these people who have been failed by Grand Junction. Campbell organizes and conducts “The Feed,” at Whitman Park every Saturday afternoon and another one at Columbine Park on Sundays. These are opportunities for homeless people in town to get a hot meal as well as stock up on snack items, fresh produce, and other non-perishable essentials to get them through another week. Cambell spoke on the primary goals of Solidarity Not Charity saying, “We bypass the system to get stuff done. There’s a lot of time these people can’t get into the system, if people don’t want to or can’t get into the system, they’re in limbo. We don’t not help people because they have a felony record, or this or that. We can bring food right then and there, if we don’t have something we’ll find a way, and if we can’t find a way we’ll find a halfway.”

Cambell stresses the importance of harm reduction in this community, something that Solidarity Not Charity exercises daily around town by offering free haircuts to the homeless, passing out clean needles, and keeping track of where most of the homeless stay at night so that they can pass out blankets and hand warmers on cold nights of the year.

Houseless man sleeps at Columbine Park during a baseball practice. Summer Fredlund/April 5, 2023.

When COVID-19 hit, Niederkrueger, a local Grand Junction group known as the Western Regional Advocacy Project, and an array of homeless advocacy groups from across the state joined together as plaintiffs and filed a Writ of Mandamus through attorney Jason Flores-Williams. This Writ of Mandamus went to Governor Polis requesting him to exercise his power as Governor to, “Commandeer or utilize any private property if the governor finds this necessary to cope with the disaster emergency.” (Colorado Revised Statutes Title 24) Grand Junction ended up being one of the only cities in Colorado that rejected the appeal outlined in this Writ of Mandamus and did not provide temporary emergency housing for the suffering homeless population. This could be seen as a major disservice and lack of care for the displaced citizens of this town, yet Cambell found a silver lining in this stressful time to allow Solidarity Not Charity to capitalize on the city’s lack of initiative.

“We needed camping, so we pushed for the city and the police department not to move anybody. We’re in an emergency in place (situation) so, if you’re telling people if they’re a risk for COVID they can’t leave their home, what if your home is outside? So they didn’t move anyone for years. Having everyone in place, we were able to connect with everybody easier. The whole radius around town, all these camps. So if somebody called us to find someone, we were really able to find them.”

Cambell has spent years witnessing the destruction that chronic homelessness brings into people’s lives as they remain stuck on the streets with no reform or end in sight.

“We see people just deteriorating. We bring in people that we think are elderly and they’re younger than we are. We brought in a lady we thought was well over 50. She was 39! You watch people die. A lot of people have died. They keep dying all the time and it kills you when you’ve advocated so much for that person and they just get turned down, turned down everywhere they go, then they die.”

The homelessness problem in Grand Junction isn’t a unique one in Colorado, however it feels much more desolate. There doesn’t seem to be as much urgency or planning going into the problem here as compared to Denver. At the same time, the statewide mental health crisis is being permeated by the fentanyl and meth epidemic spreading into the community.

The mental healthcare crisis is a major aspect of what often keeps the chronically homeless of Grand Junction stuck in their situations. In the case of many of the homeless population, the guidance and resources to get proper mental health services are nowhere near available to them. Many end up going to Mind Springs, a mental health care center that is partnered with the Coalition for the Homeless, that has seen a very fair share of heat in the media in recent years.

A report from The Aspen Times in March 2022 outlined some of the shocking controversy surrounding a state investigation into the health care center that, “Found a sample of 58 Mind Springs outpatient clients, nearly half of which received a quality of care so poor that it was categorized as having, ‘potentially severe, life threatening impact.’ Two died.” The report also details instances of impractical and dangerous medical prescriptions being handed out to at risk patients.

To further back up these findings, Green Faith Minister Grueling coined himself a “Mind Springs Survivor,” during our interview at Whitman “Bum” Park, outlining a similar tale of ignorant pill prescriptions and unfocused medical care. Grueling’s prior story of passing out outside of Catholic Outreach’s transitional housing was caused by an unhealthy and far too consistent dose of Klonopin that Mind Springs had prescribed him during his homeless years that the facility never altered or provided follow up. Describing a “downer,” Mind Springs had prescribed him, Grueling said, “I looked up the sleeper and in big old block letters it said, ‘Do not prescribe for more than ten days,’ not four and a half years! So needless to say I quit, right then. Talk about withdrawals. There was about six weeks I don’t even remember.”

As for Pooka Cambell, Eric Niederkrueger, and Solidarity Not Charity, their hopes for the future are that people can approach this homelessness problem with less inequality and more compassion.

“I would want everybody to advocate not repeating the past. Poverty has been around for so long. Can that be something, like all these other (social) things we’re fighting for now, can we all come together and just try to stop it?” Cambell said.

It has been proven through dozens of accounts and statements made throughout the course of gathering interviews and data for this investigative report that the displaced and chronically homeless are often the forgotten and swept aside citizens of Grand Junction. A rallying call from citizens resulting in more people getting involved in radical help efforts and community harm reduction would certainly go a long way, however, change must be made from a state and city government level as well.

Grayson, 22, stands on the corner of 5th and Pitkin. Grayson has been unhoused

since 2022 and plays instruments on the streets to make an income. Summer Fredlund/March 12, 2023.

The ongoing problems with chronic homelessness in Grand Junction stem from the public stigma of fear and stress when confronted with the realities of homelessness, the city’s slow reactions and poor decision making when dealing with these issues, as well as deeper problems of drug abuse, job insecurity, and the very poor mental health services to be found here. Solidarity Not Charity’s efforts need further support in order to enact true change in this community. This epidemic of chronic homelessness is a dense problem with no clear cut solution, especially with the political and social dynamics that surround it. A massive increase in affordable housing and health services have proven to be two essential changes that could start to even out this severe problem. In the meantime, Grand Junction residents can help out at Solidarity Not Charity feeding events at Whitman Park on weekends, as well as make their voices heard about this ongoing issue at city council and Coalition for the Homeless meetings.